← Projects

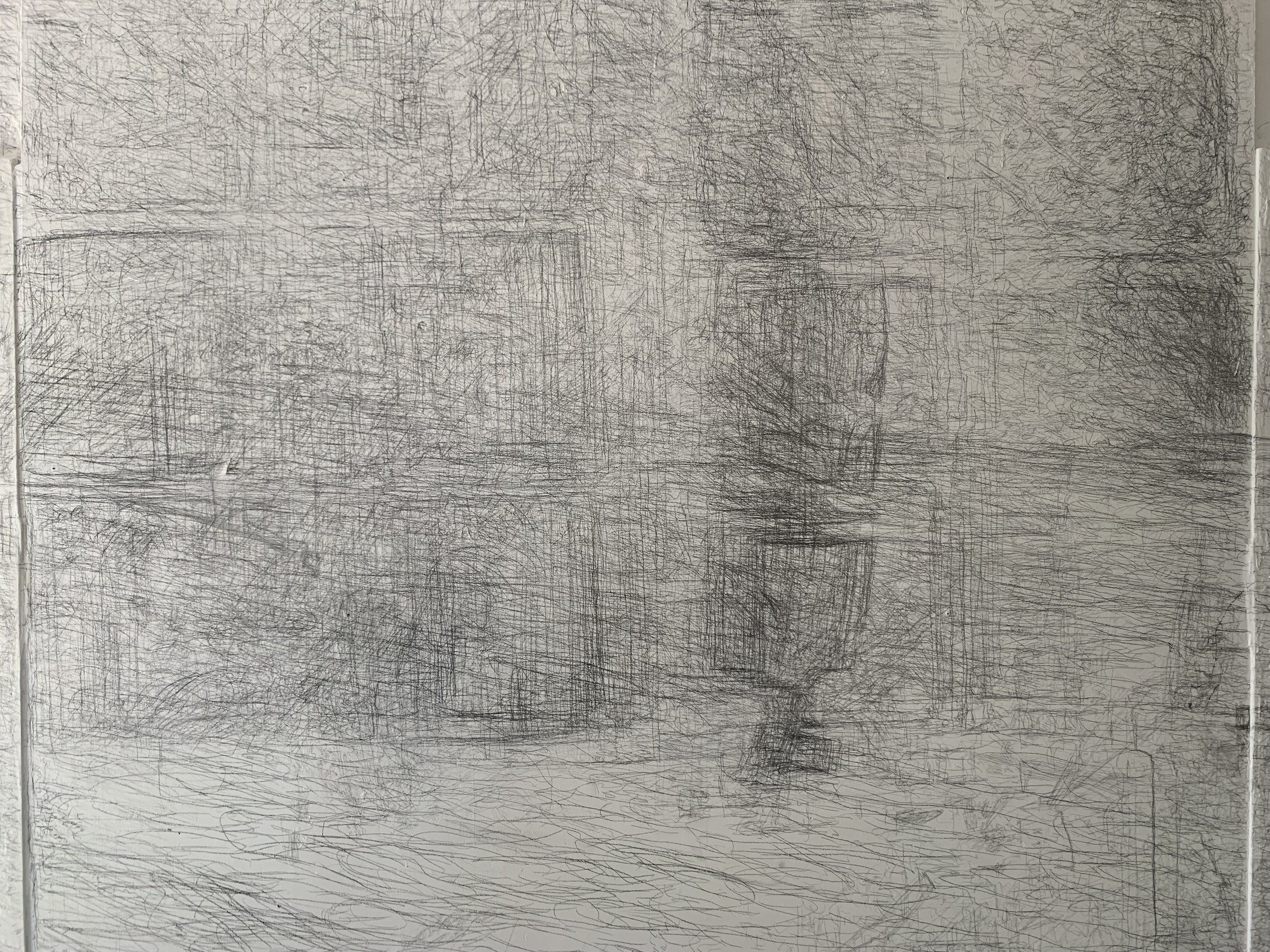

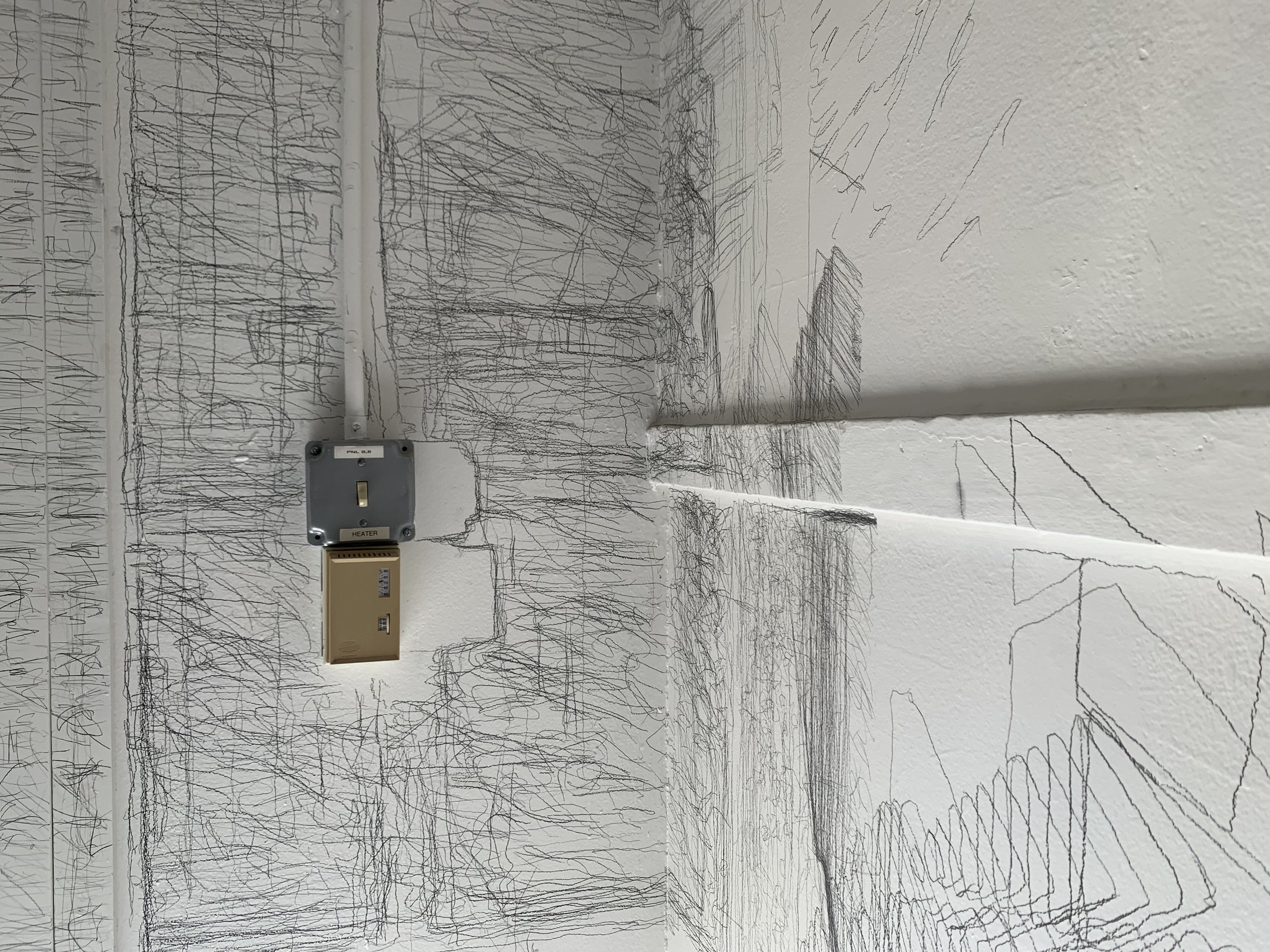

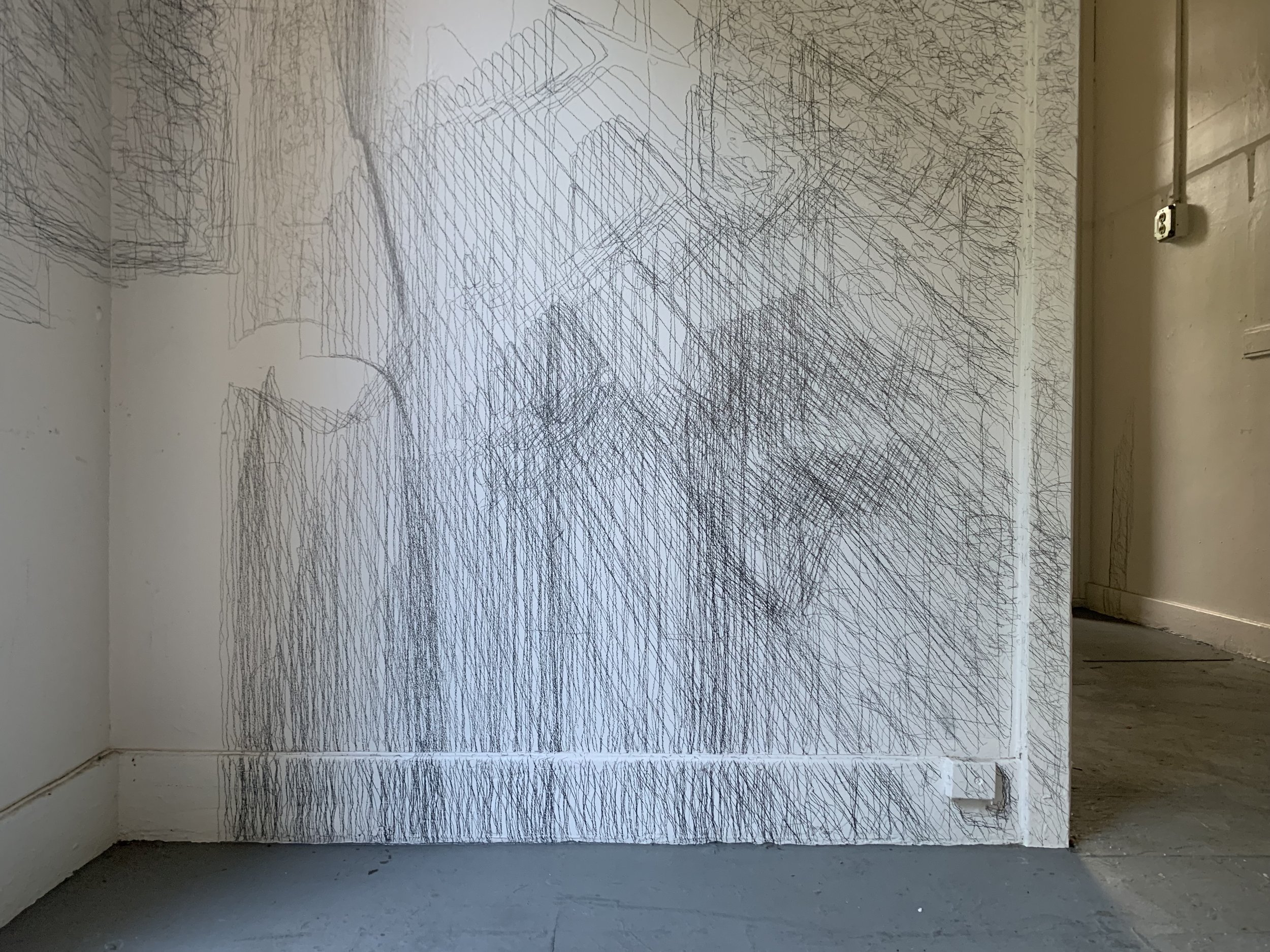

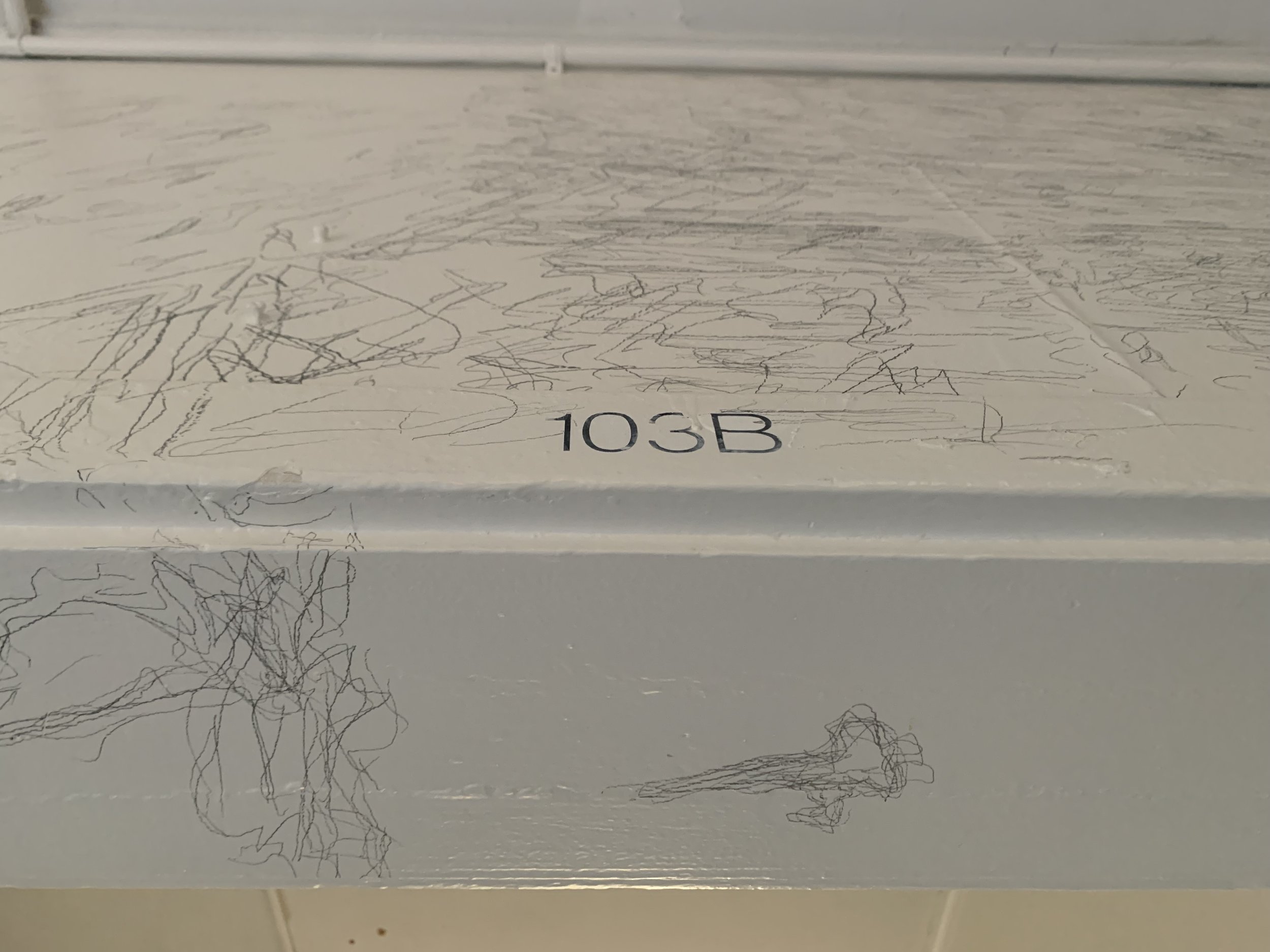

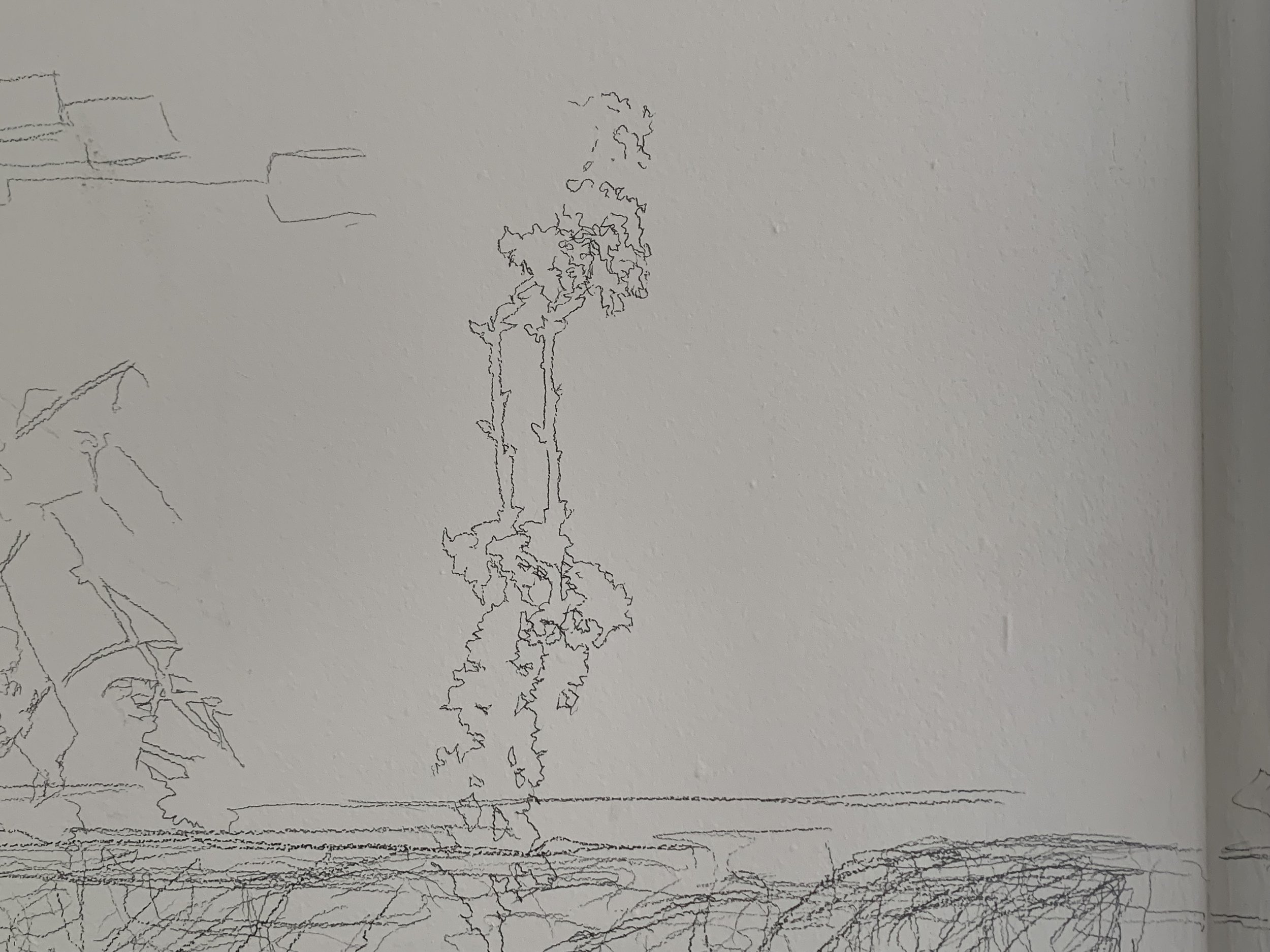

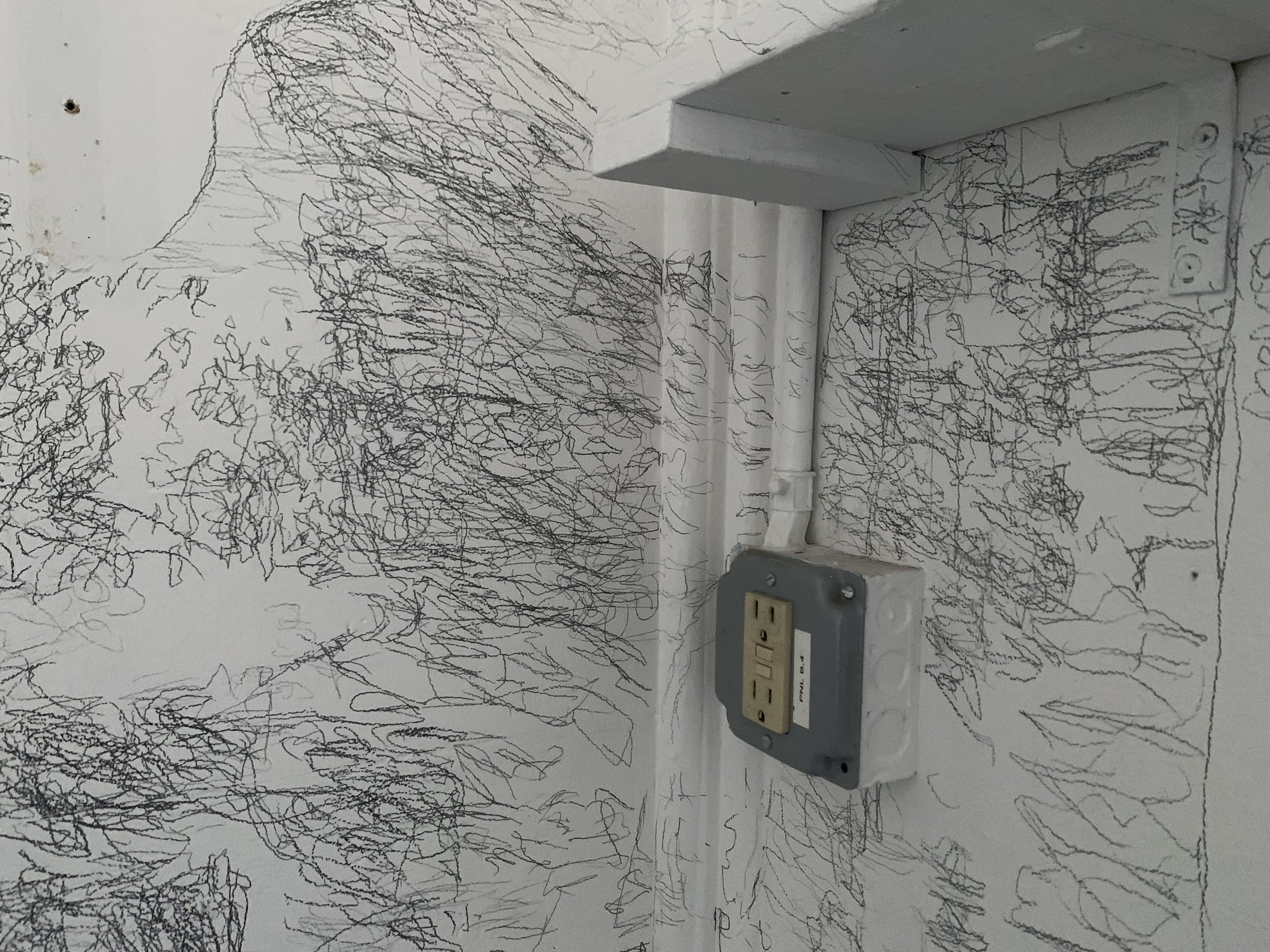

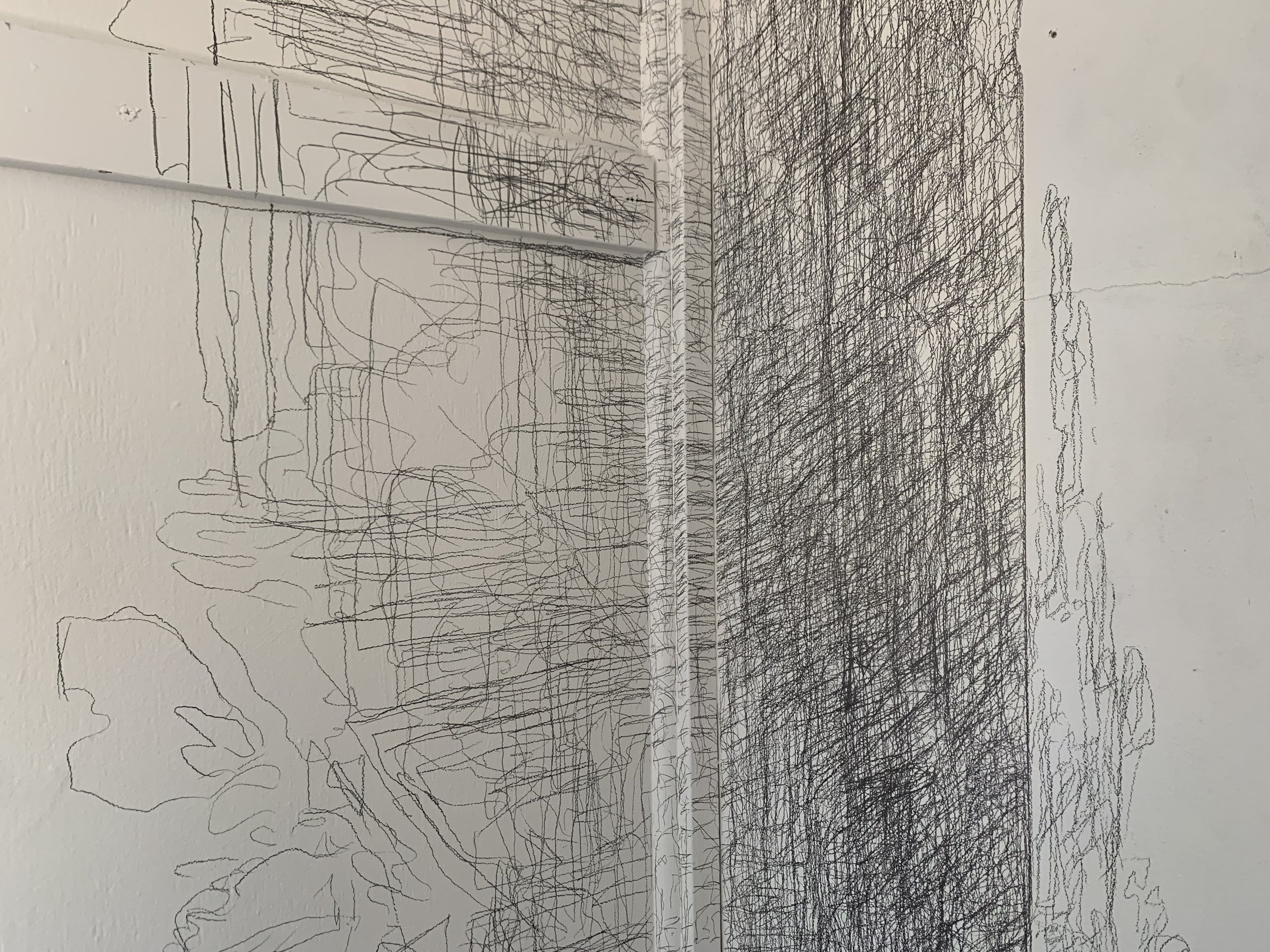

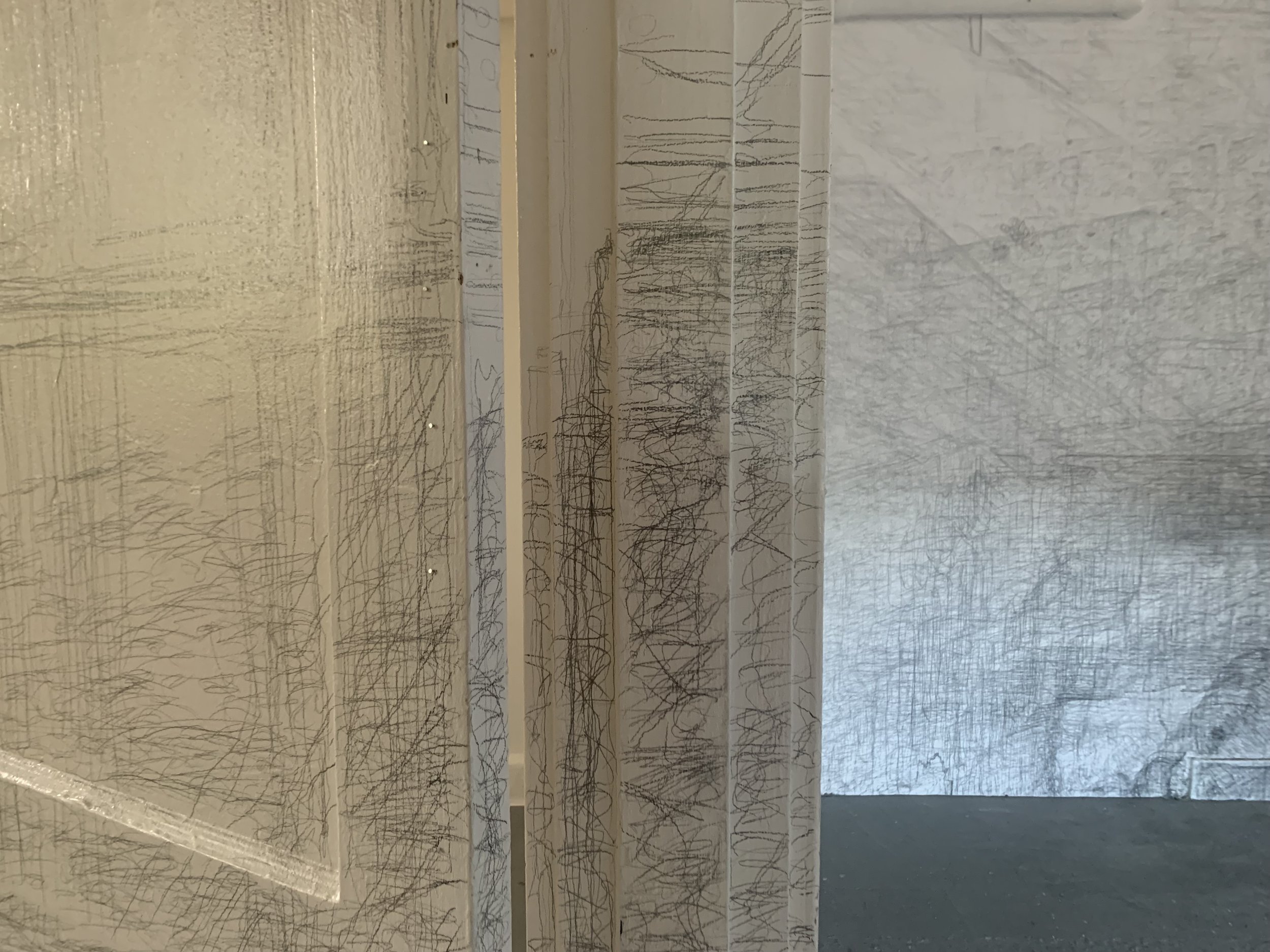

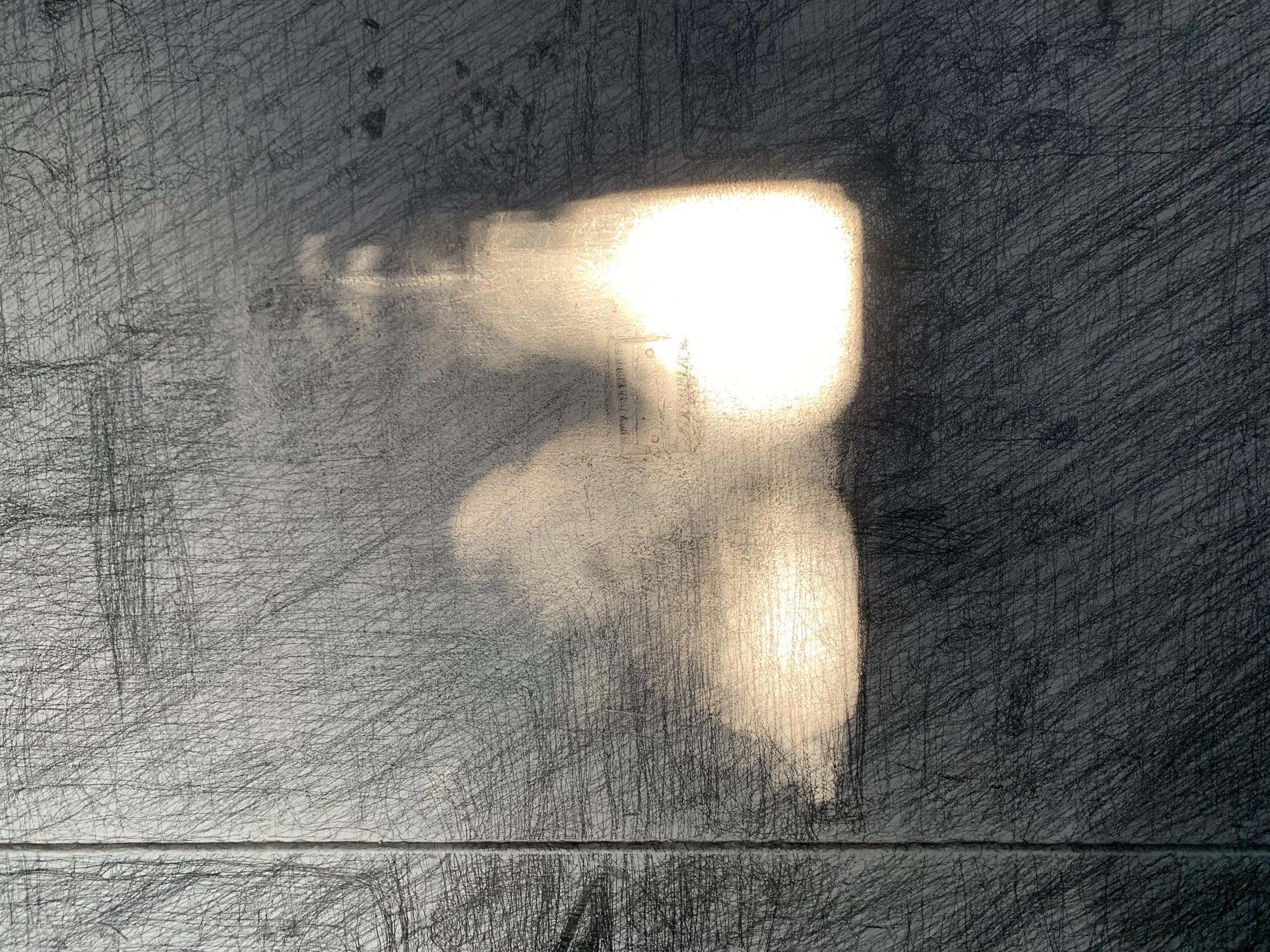

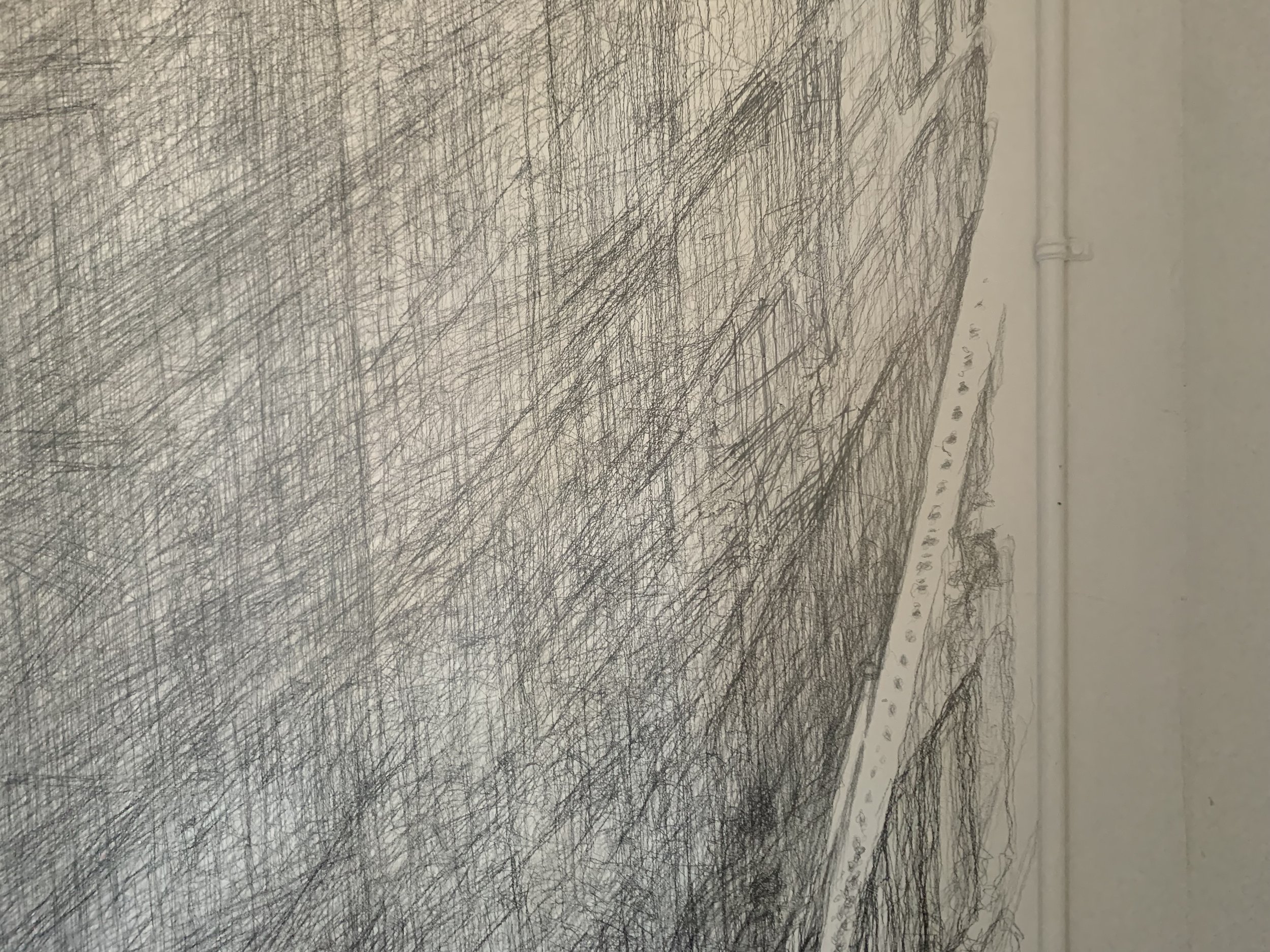

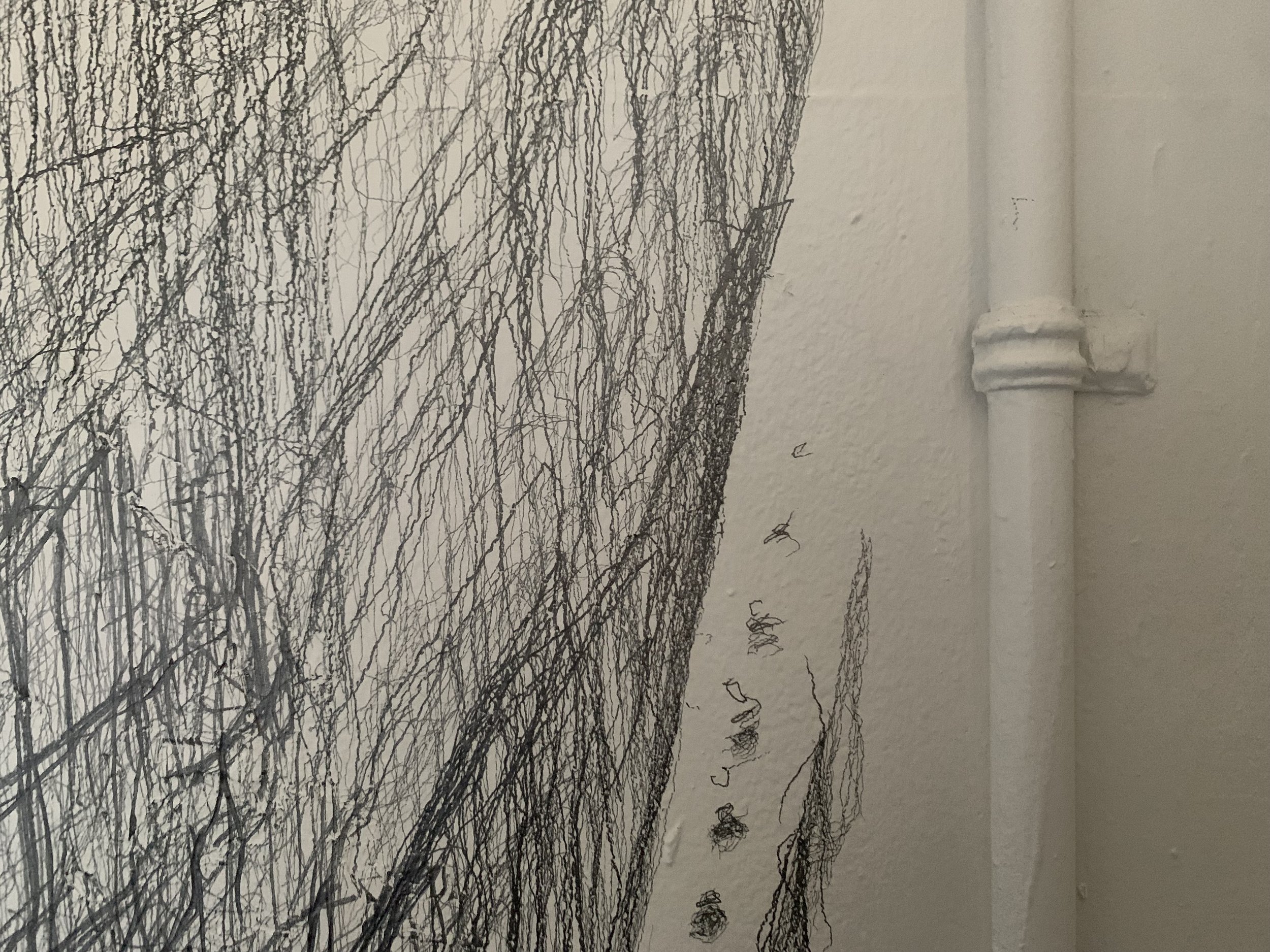

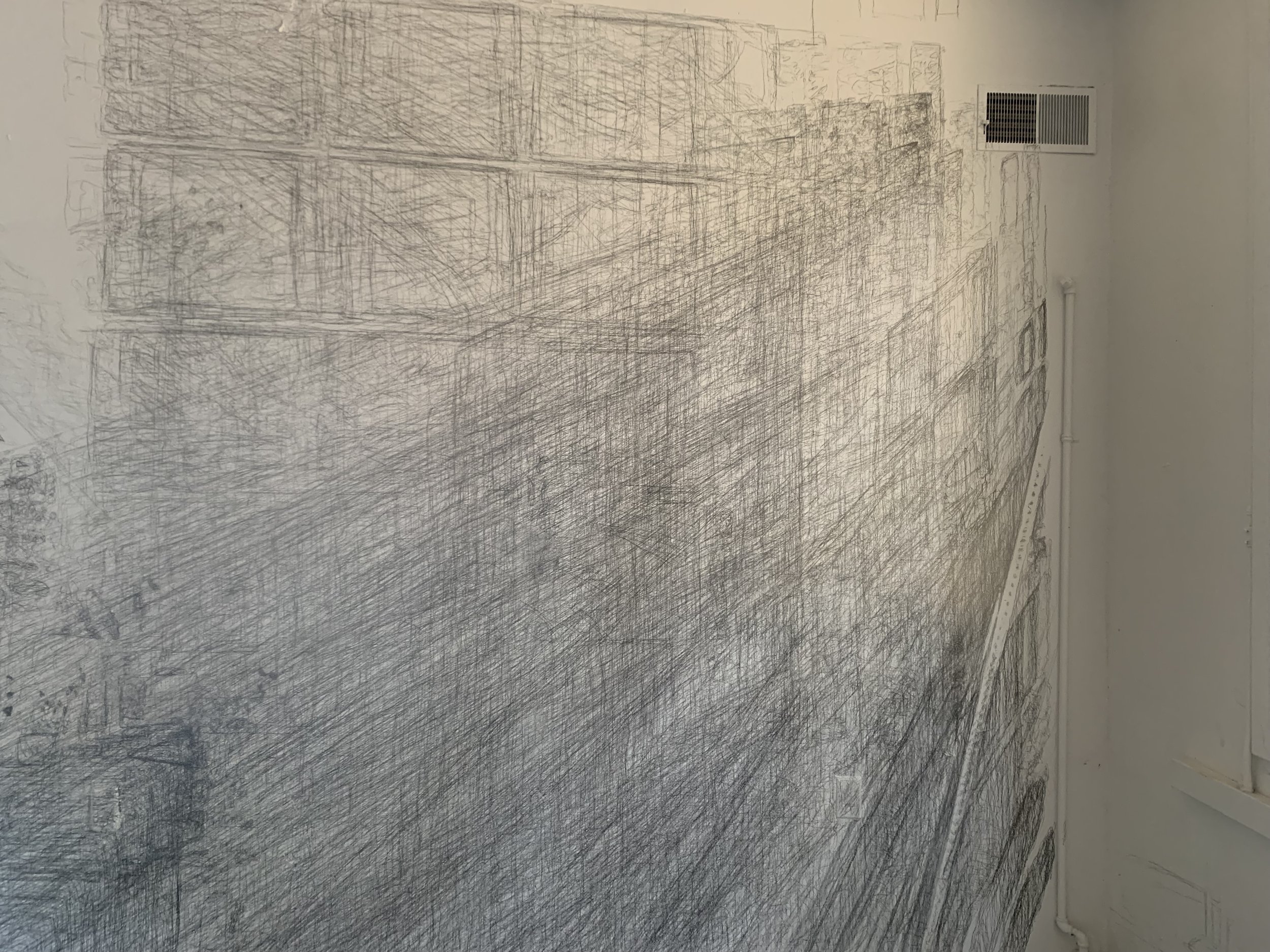

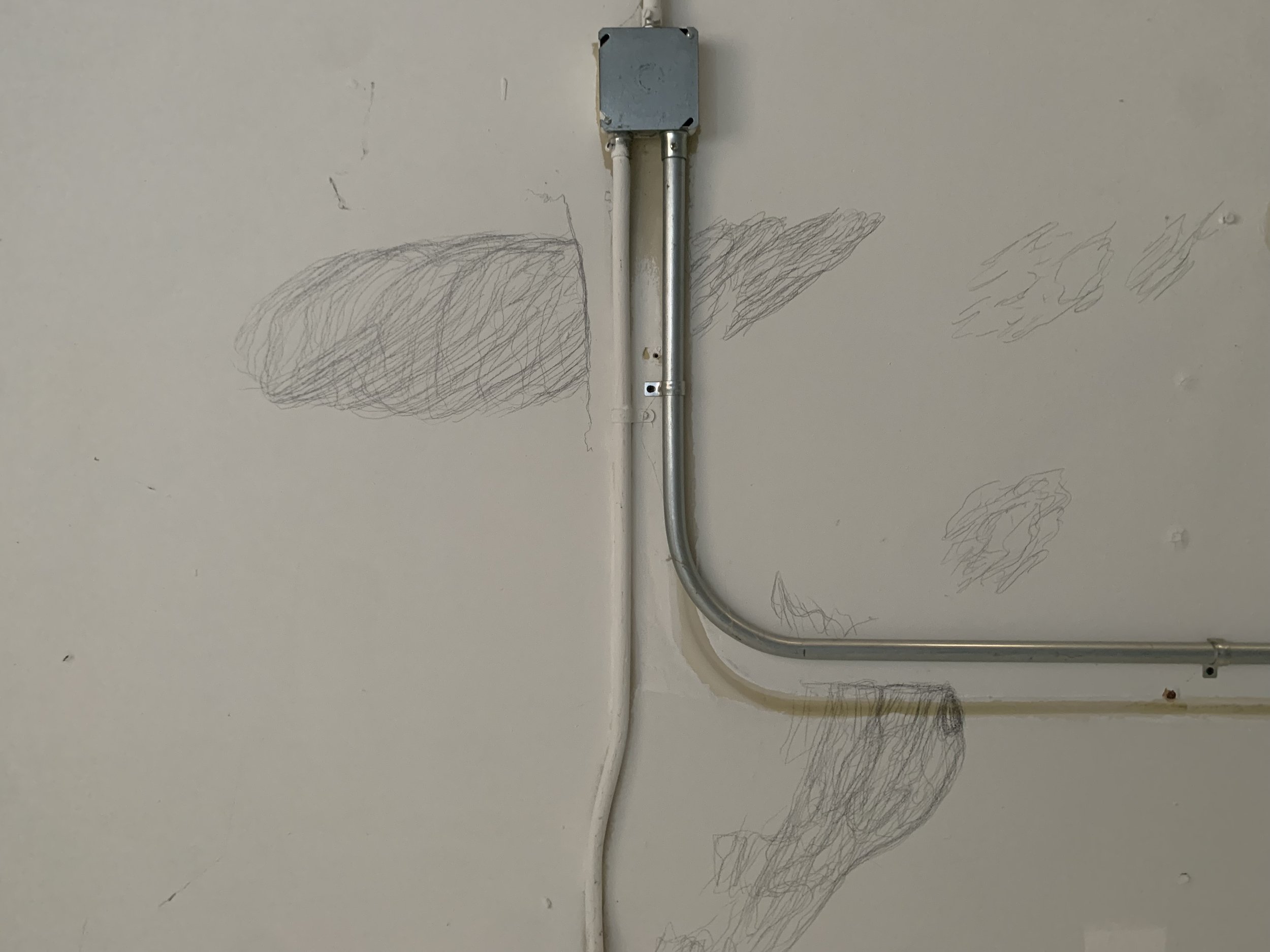

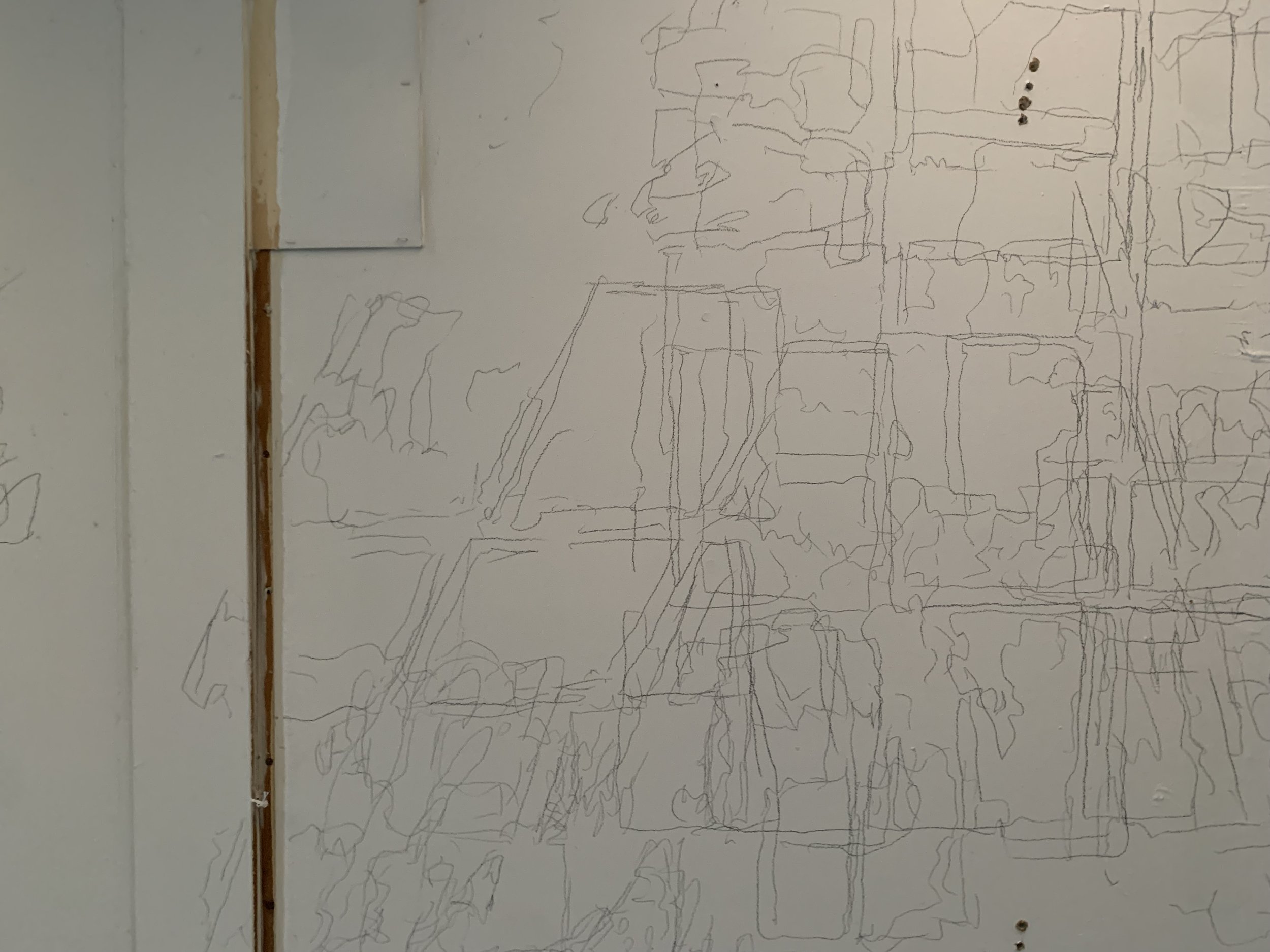

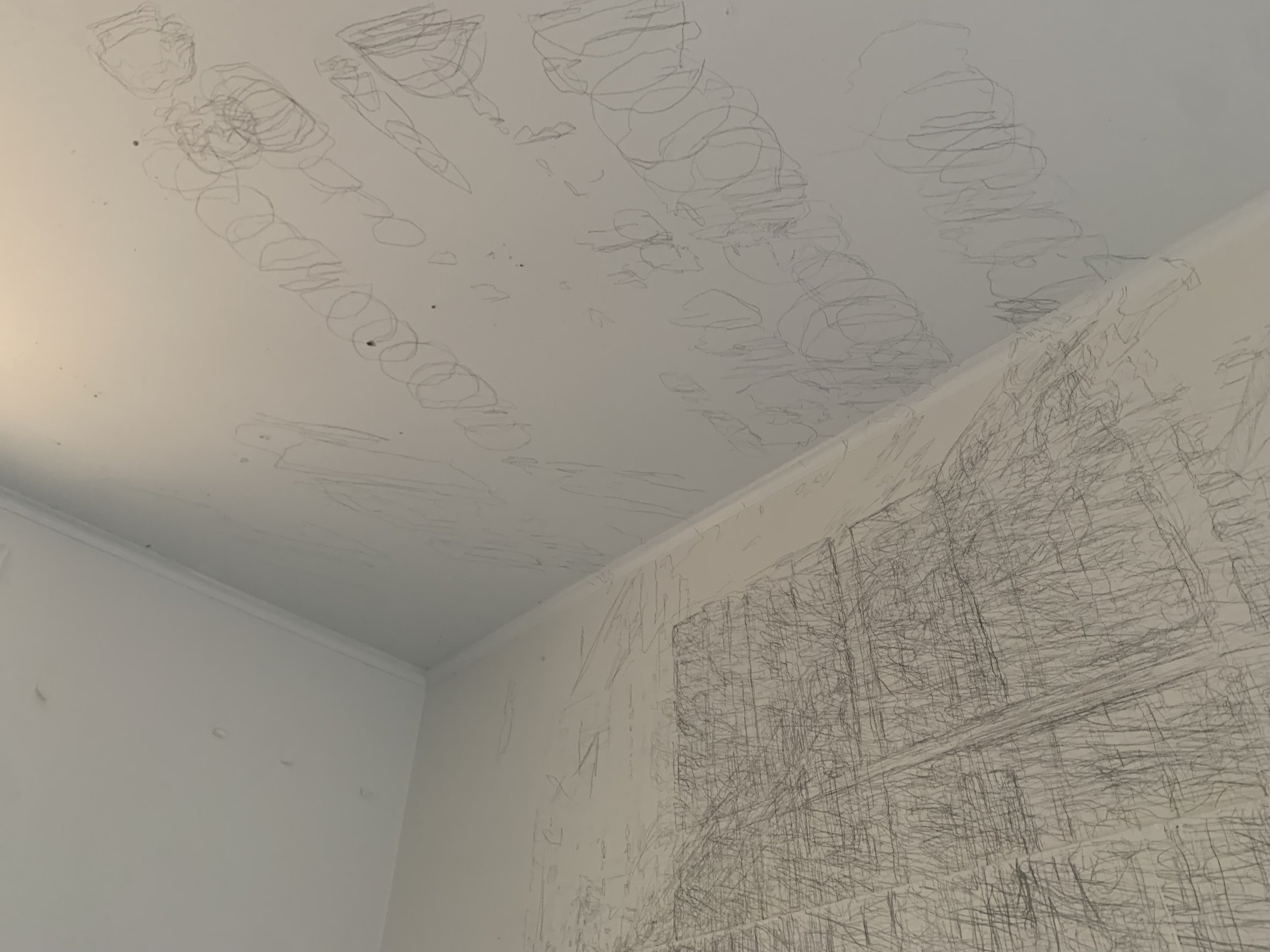

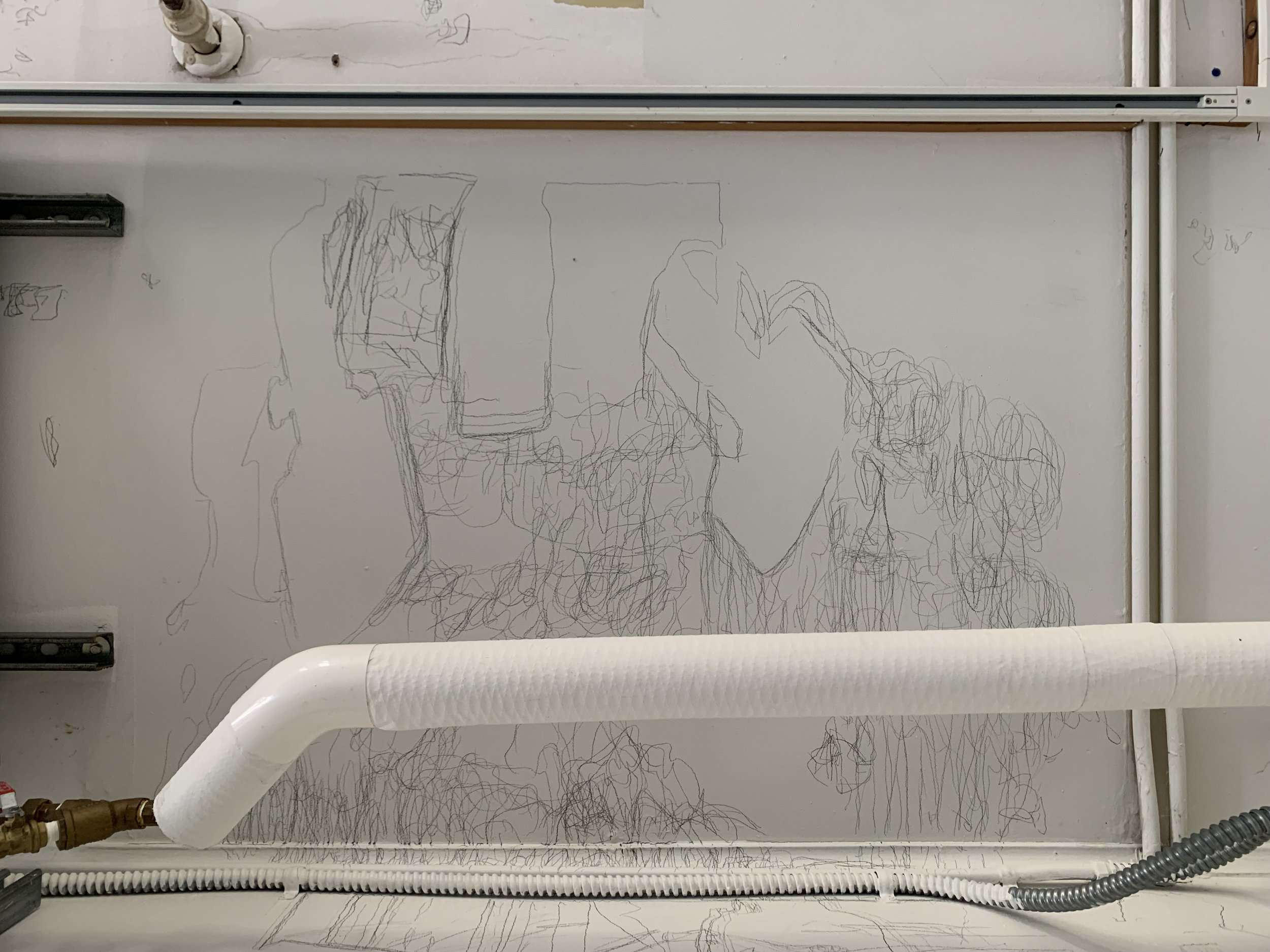

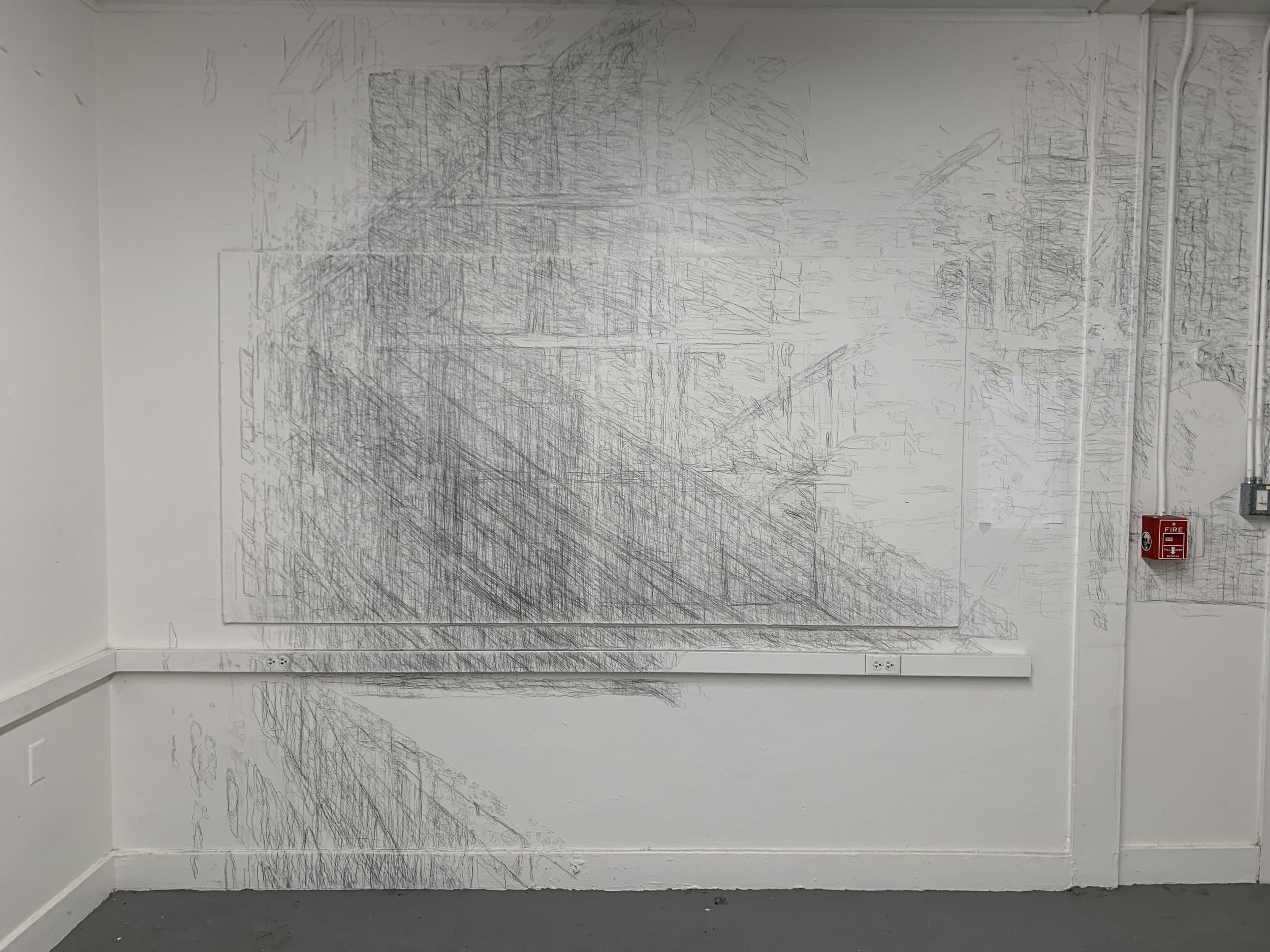

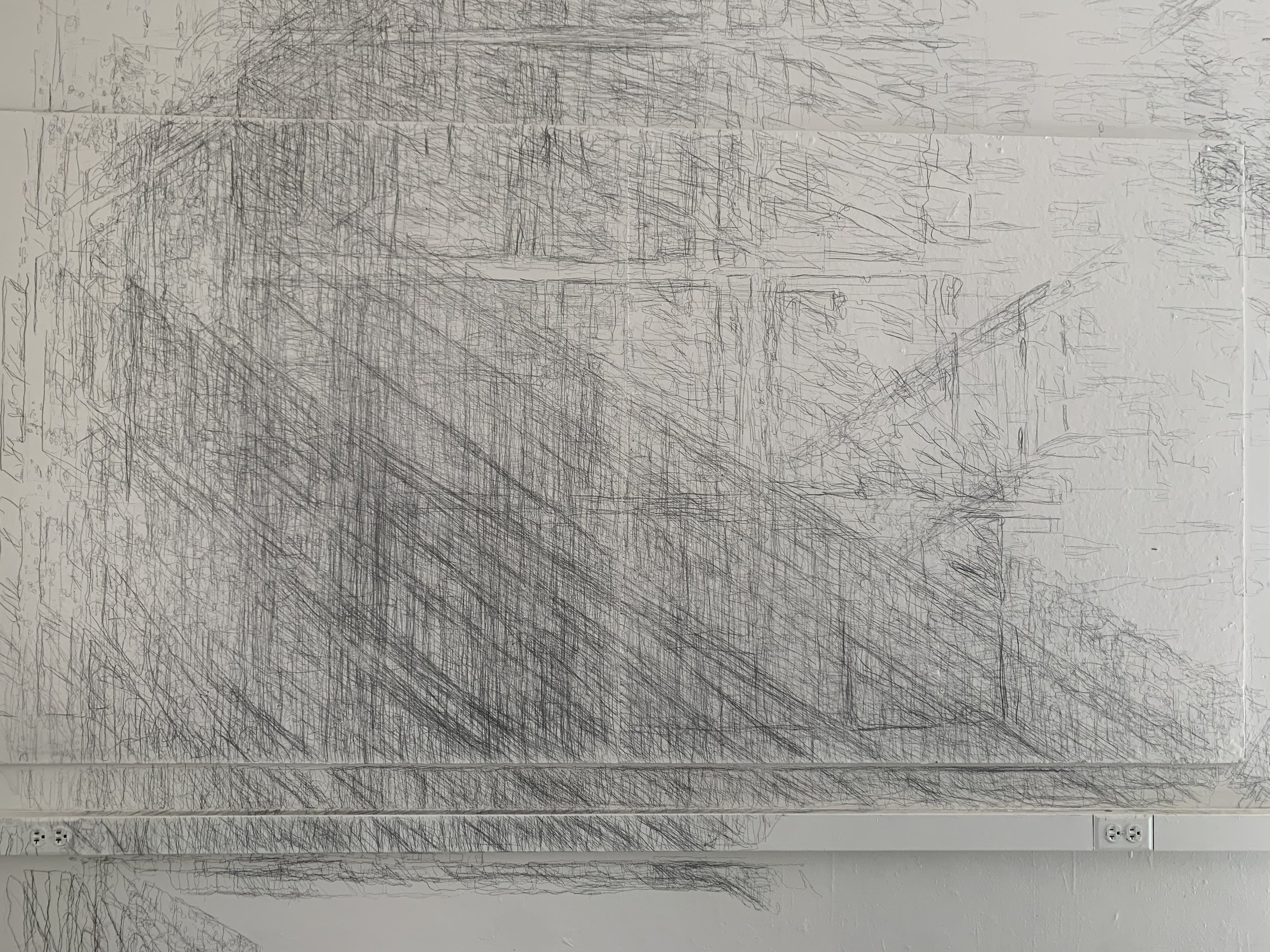

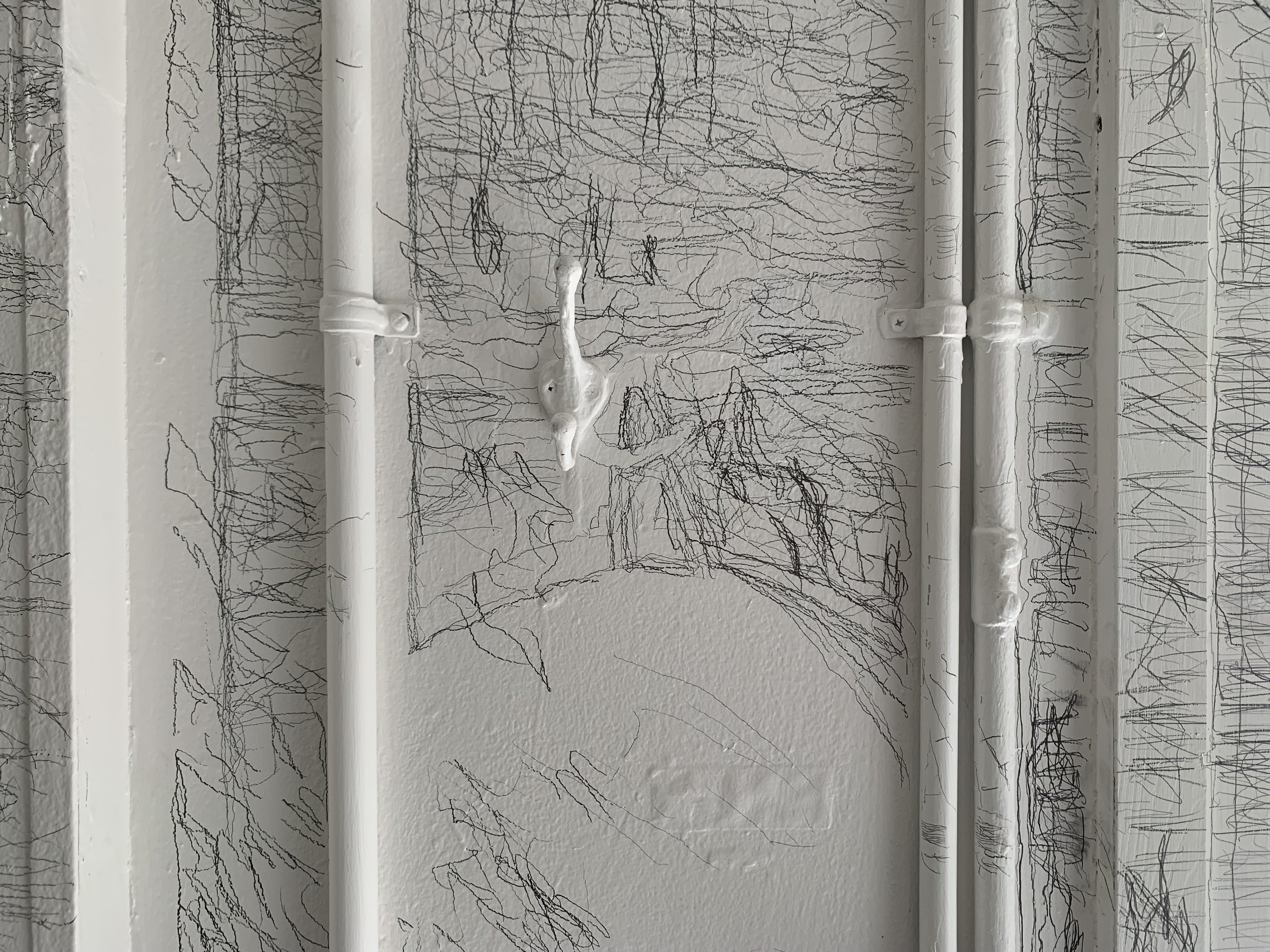

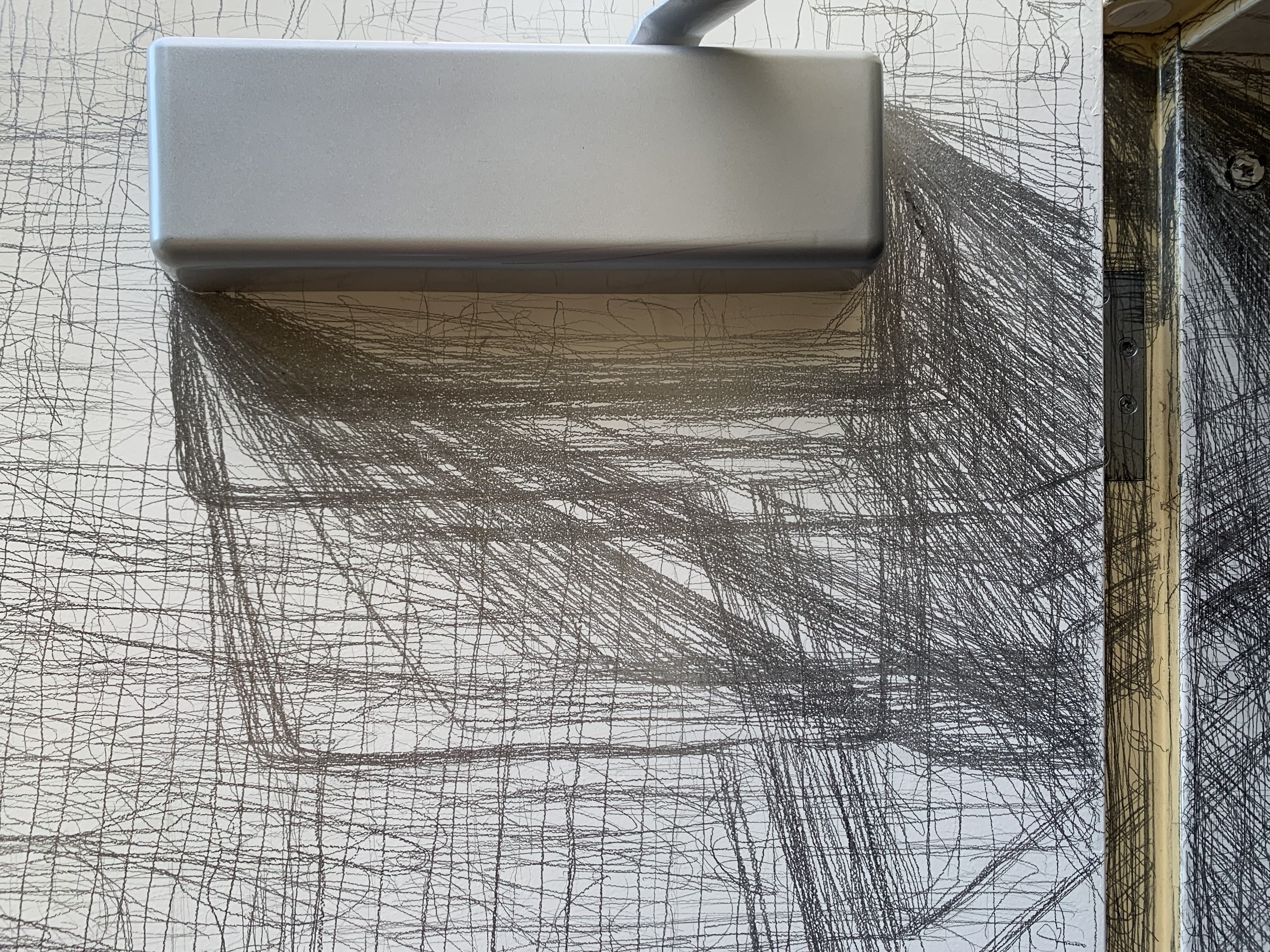

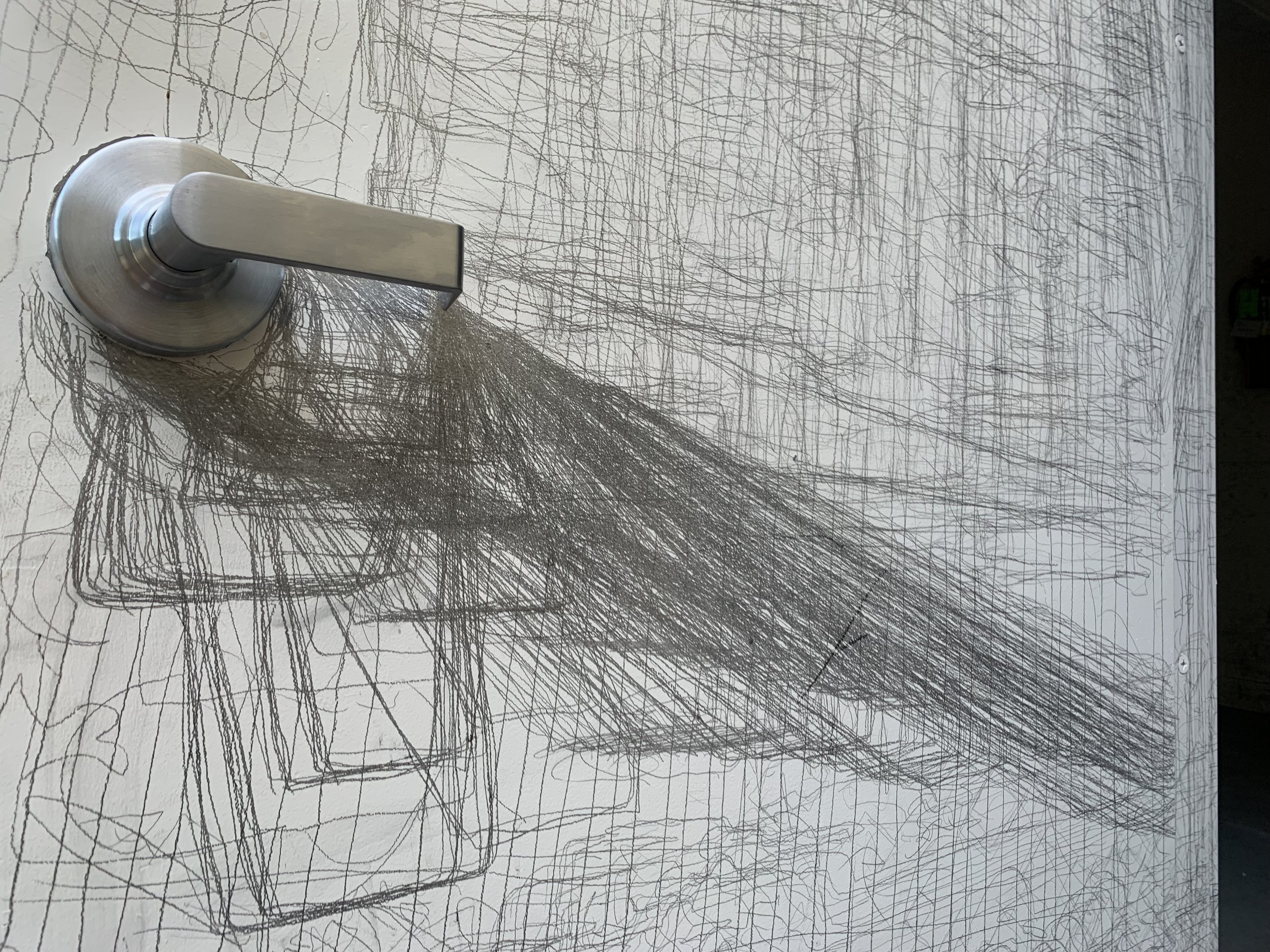

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variableImpressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

Impressions Lasting, 2022, Graphite on architectural surfaces, Dimensions variable

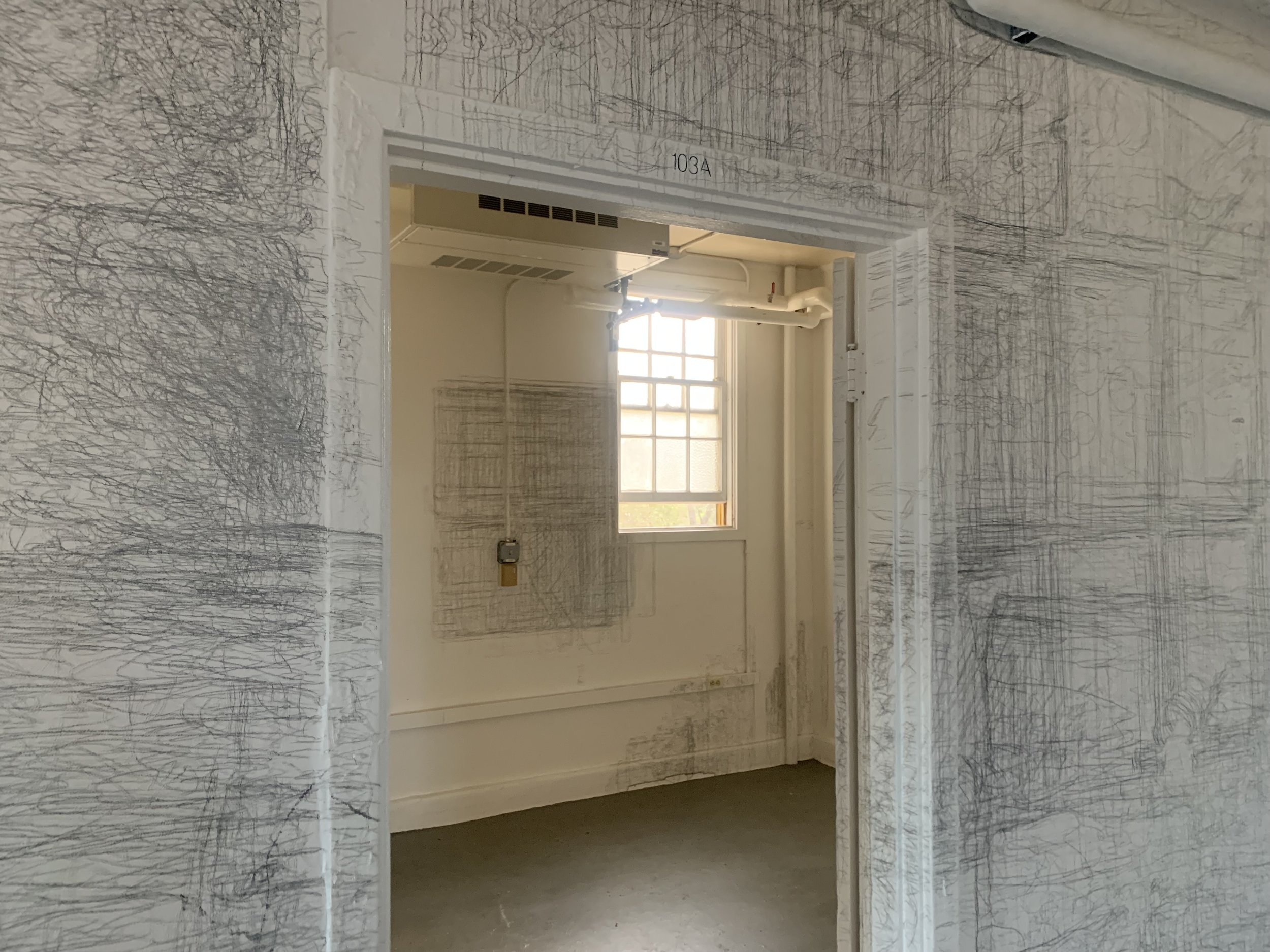

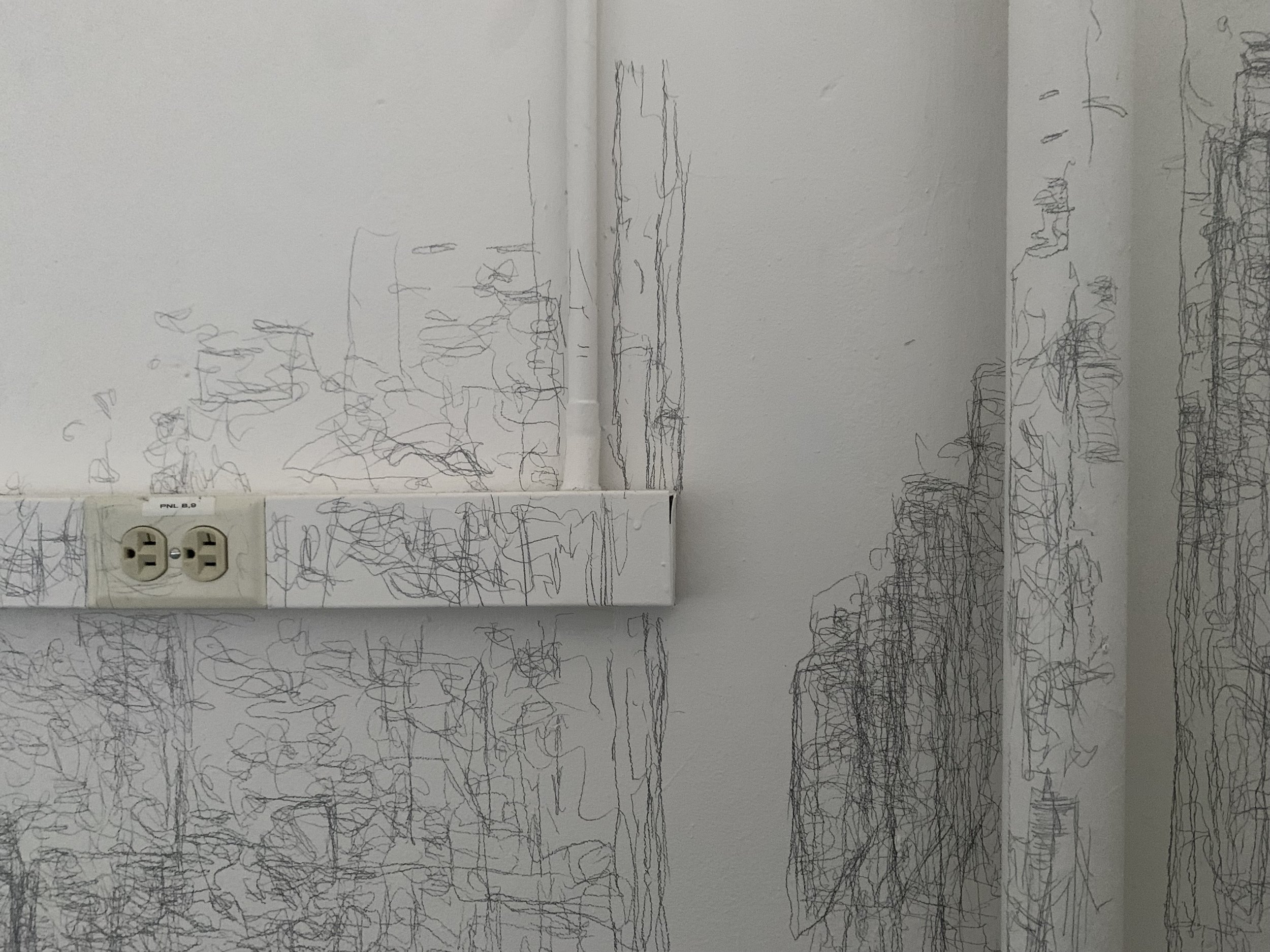

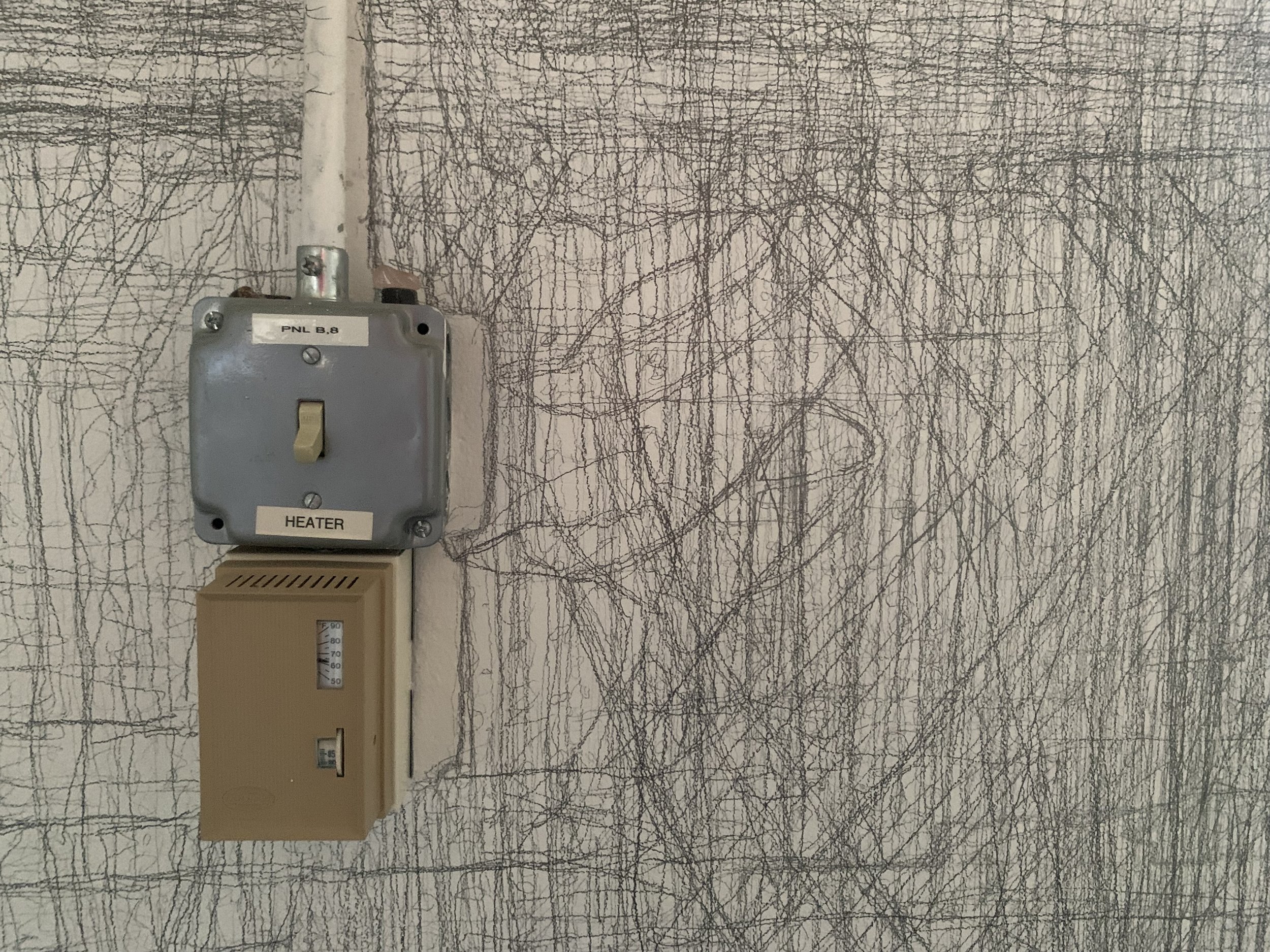

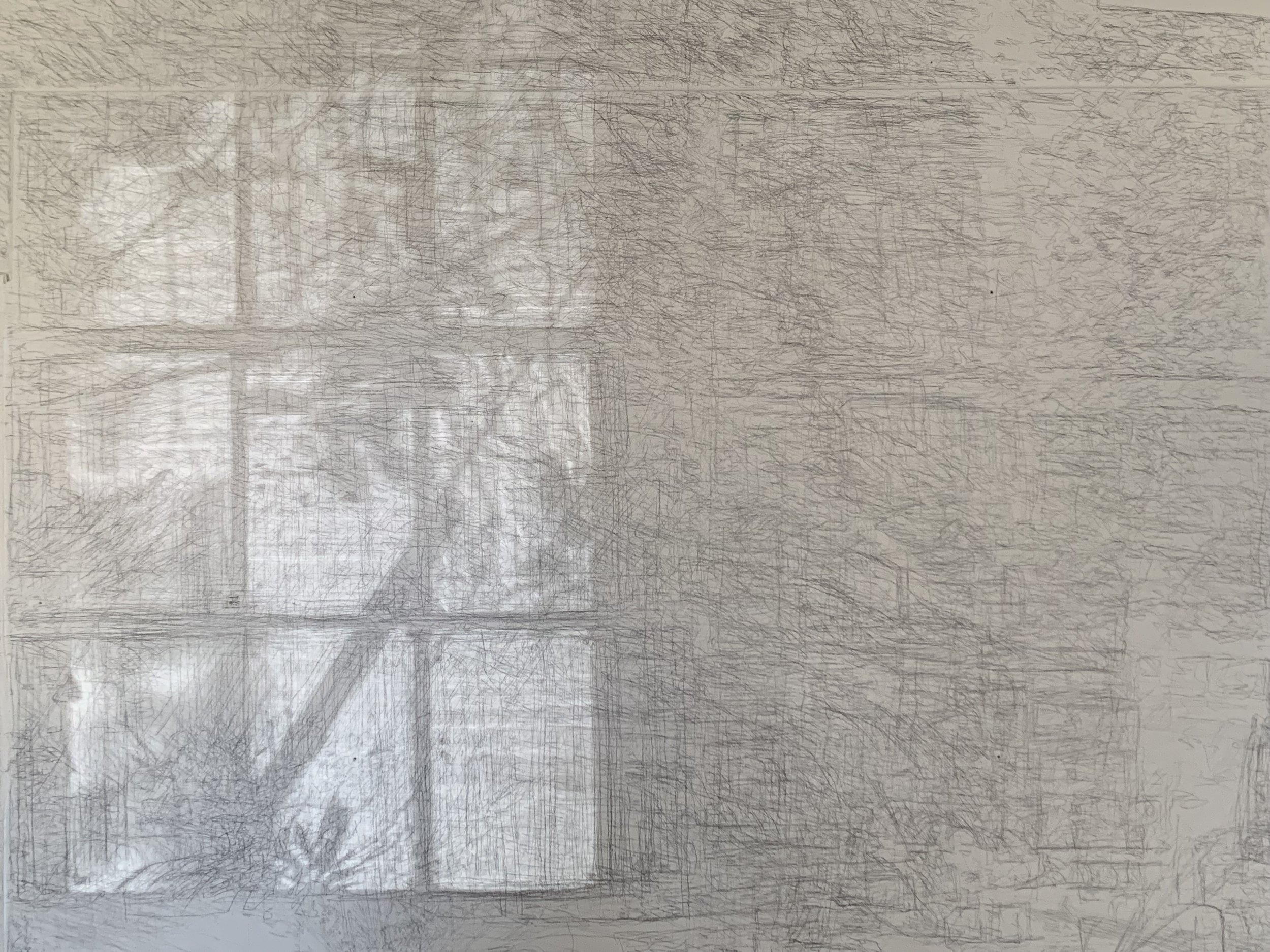

In Impressions Lasting, I created graphite drawings on the walls and ceiling of my studio made by accumulated tracings of sunlight and reflections that appeared within the interior space. The drawings document the earth's complete rotation around the sun, expressed by the shifting light of my studio throughout my last year in the MFA program at Stanford.

Joshua Moreno Traces the Light

By Adin Walker

“I am tracing the light daily, as it moves throughout my studio.” As he says this, his fingers run across the lines of graphite along the walls, creating tiny smudges. His eyes catch the light, too, and the artist himself starts to disappear into the work. Indeed, as I look upon the tracings, I start to become more aware of the artist’s body – the lines and smudges document how the light hit as well as how the artist moves within his studio. Some of the tracings are darker and sharper and seem to indicate that, on those days, he traced with more vigor – or, perhaps the light was more saturated. Other areas suggest a more lithe hand, perhaps to match the delicacy of the light on those particular days and times. But it all keeps changing. The light, the graphite, the body of the artist. Nothing is permanent.

Moreno’s tracings enact performances of disappearance in which the artist becomes understood through the ephemeral logics of light and time. What is art, then, but a trace of phenomena outside of and beyond our bodies? The act of tracing becomes an act of mourning, and suddenly I understand Moreno’s work to be a meditation on loss. I sense in Moreno’s art a kind of grieving for his own body as it ages through time. Yet, within that mourning of the body is a larger performance of grief for our planet – the tracings strive to archive and remember the light because we do not know when, if, or how the lights will one day go out. In this way, Moreno’s work intersects with larger discussions of the Anthropocene. A critique can be found in Moreno’s work reminding us that we live our lives following the light – the networks of resilience which, if we immerse ourselves into studying, learning, tracing, and honoring, will aid in our abilities to endure the daily pain of living through loss and grief that comes to shape being human.

And, in other ways, the daily pain – and joy – of being queer. When I take in Moreno’s work, I am reminded of José Esteban Muñoz’s notion that in order to perform queer historiography and seek out “evidence” of queer life and love, we must employ an “hermeneutics of residue,” look for the remains, debris, shimmers, and stickiness to help us understand the historicity of queer life that precedes us. Moreno shows me a big graphite smudge where he notes that someone hanging out in his studio one night must have slid up against the wall. If the lines indicate how and when Moreno traced the ever-changing light, then the smudges indicate when Moreno opened up his studio to more light. To friendship.

← Projects